David Bokan

Spatial Navigation on the Web

bokan@chromium.org Google Doc

Background

Spatial Navigation is an input modality that allows mouseless navigation around a page using directional keys. In this mode, the keyboard arrow keys (or a “DPad”, remote, or joystick) cause an indicator on the screen to move from one interactible element to the next in the direction of the pressed key. This mode is typically used on devices that don’t support pointing devices like a mouse or touchscreen. Examples include TVs and set-top boxes but can also be used by users who’d prefer to use a keyboard or cannot use a pointer.

Current State

Chromium has an existing spatial navigation implementation (the only browser as far as I’m aware). This mode is not enabled by default, it requires passing –enable-spatial-navigation on the command line. This has been implemented and maintained by various vendors including Nokia, LGE, Google, and others. An effort to standardize and extend this implementation is on-going in https://github.com/w3c/csswg-drafts/labels/css-nav-1 with additional details in https://github.com/WICG/spatial-navigation. The latter repo includes a JavaScript polyfill of the spatial-navigation spec.

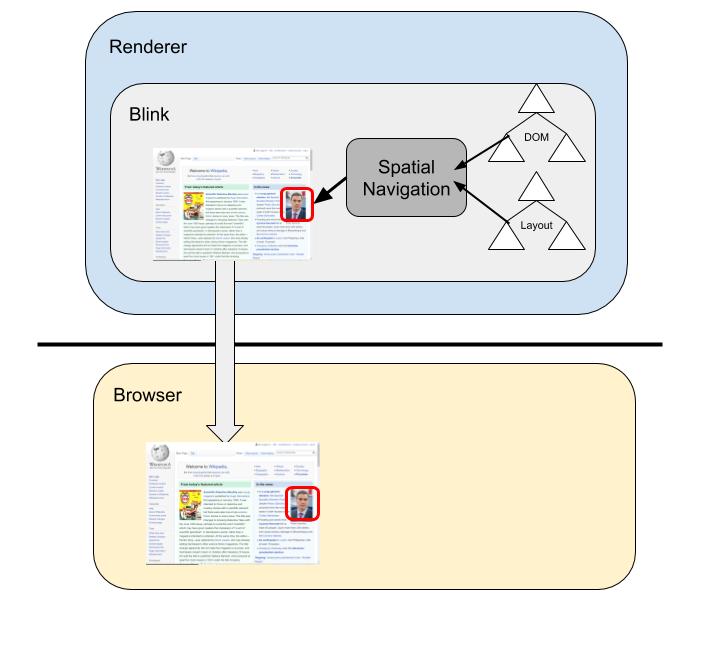

Chromium’s Spatial Navigation functionality is implemented directly inside of Blink. It operates by traversing the DOM and Layout trees directly and moving the page’s focus. As such, it is entangled with page content. However, pages lack any direct APIs to interact with spatial navigation, relying on existing DOM events and functions. The APIs mentioned in the links above are not yet implemented. This is problematic because the APIs that do affect spatial navigation are frequently used for other purposes. For example, some pages programmatically move focus around the page using Element.focus(). Others, handle and consume KeyDown events, preventing spatial navigation from operating.

The proposals above attempt to fix some of these issues and provide authors with an extensive set of APIs, allowing them to build rich spatial navigation UIs on the web.

Proposal

In my opinion, the above proposal is attempting to solve two problems that are in tension with each other. The first is providing a framework for building first-class spatial UIs that are rich and deeply customizable; e.g. apps built for use on a smart TV. The second is allowing spatial navigation of the wider web; the vast majority of which is not designed or tested for use with spatial navigation.

These often have opposing requirements and goals. When spatially navigating the general web (either through a pointerless device or as an assistive technology), users require a consistent and predictable experience. Providing extensive customization is counter to this. Additionally, interaction with page APIs and concepts also hurts this goal since it risks pages inadvertently breaking the experience. For example, YouTube widgets (conveniently, in non-spatnav cases) override arrow keys to scrub back and forward in the video timeline, breaking spatial navigation (more examples in this Doc)

On the other hand, there are cases where a rich spatial UI is desirable. TVs, game consoles, and other specialized devices should be able to build applications that are optimized for directional input. These applications require a rich, expressive feature-set and an ability to innovate quickly. What they need is a spatial UI framework; they would be ill-served by a slowly iterating, limited browser implementation.

I propose the following: treat these two use cases as separate problems with separate solutions.

General Web Browsing

For general purpose web browsing, the existing spatial navigation implementation should be moved out of the rendering engine and into a separate browser component. Its behavior should conform to the navigation algorithm specified in https://drafts.csswg.org/css-nav-1/. However, It should provide less interaction with pages (i.e. no more moving of focus, using CSS outline).

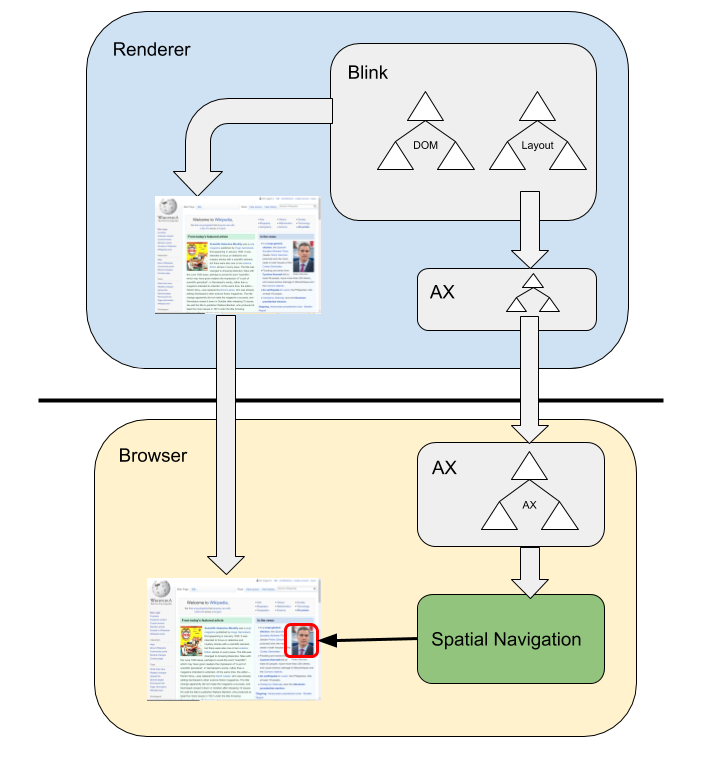

One idea is to turn this into an assistive technology that consumes the accessibility tree (credit to the Microsoft Edge team and Rossen Atanassov, who described this as Edge’s approach to the same problem). This would allow spatial navigation to leverage all the work already done by accessibility tooling for interpreting complex, arcane DOM structure into its semantic meaning. Limited customization and hinting would be provided using ARIA roles. This would have the benefit of being more general as well as encouraging the creation of more accessible content.

Chromium implementation-wise, here’s a rough sketch of how this would look:

Before

After

This has the major benefit of being off the browser’s main thread. Today’s spatial navigation implementation runs entirely on the main thread where it competes for cycles with the rendering lifecycle, and worse, page script. The result is a high-latency experience for users. An external spatial-navigation component would be far more performant.

Additionally, it would be easier for different vendors to swap in their own improvements or entirely alternative modules.

Building Spatial-First UIs

For the spatial UI case, the framework proposed in css-nav-1 has many great ideas and features and is designed based on extensive experience with spatial UIs. We should aim to implement this proposal as a JavaScript library/polyfill.

The FAQ at [https://github.com/WICG/spatial-navigation] lists several reasons why a browser implementation is superior. However, the explainer also references the The Extensible Web Manifesto [https://github.com/extensibleweb/manifesto]. In the spirit of the extensible web, I propose we instead find pieces missing from the web platform that make this difficult and expose those instead. We should add the fundamental missing primitives to allow libraries like this one (and others) to be successful.

As an example, one given reason against a JS library is: “Difficult to align native scroll behavior when moving the focus to an element out of view” - missing primitives related to native scrolling behavior would be simple and largely uncontroversial to add. It would additionally provide benefits to use cases outside of this one.

Another counterpoint is performance overhead. I believe this mostly pertains to the general web browsing case which this library would no longer apply to. If an author is building a spatial UI, it would be trivial to mark interactive nodes of which there should be few, relative to the entire DOM. Without having to crawl the entire DOM (not cheap, even if implemented in the browser) this should be trivially performant. JS bindings add some limited overhead but on this scale would be imperceptible to users.

This approach has several advantages, both for the spatial navigation spec and for the web platform:

-

Faster to iterate and innovate - browser features require an order of magnitude more cost to implement and maintain compared to external libraries. This is largely due to the high complexity of browser engines, requirements of maintaining legacy behavior, and high bar for standardization. In addition, the world has a limited number of browser engineers with varied priorities. Contributing to a browser engine is a high-bar to clear. (e.g. just checking-out and building Chromium can take a full day)

In contrast, it’s simple to open a GitHub pull-request against https://github.com/WICG/spatial-navigation and add a new feature or fix a bug. New ideas and features can be added without blocking on the glacial pace of browser development

-

Immediately interoperable - This would work on all browsers pretty much straight-away. Full interoperability, even for highly prioritized features, can often take years or decades and is often never reached.

-

Reduced maintenance cost and flexibility - once shipped, web features must effectively be supported forever. By contrast, pages can host their own copies of the library. This means breaking changes are easier to make and maintenance requirements less stringent. Improved layering - UI patterns and trends can change quickly. By providing building blocks, rather than baking a UI framework into the platform, others can innovate quickly and we don’t cement today’s UI patterns into the platform forever.

-

It also allows browser vendors to focus on what they do best: providing performant, basic building blocks. Browser’s aren’t known for their responsiveness to fixing issues - the ability for a broader community to maintain this would be beneficial to both.

-

We can always reevaluate in the future - perhaps after some time the API stabilizes and becomes popular through proven, successful use and the demand and performance requirements change the cost-benefit calculus above. That seems like a better and less risky place from which to add this to the platform.